Water as a source of pathogens in healthcare facilities

Water and wet environments in hospital and healthcare facilities may promote the growth of microorganisms (i.e. bacteria, fungi, and protozoa), and harbor waterborne pathogens that pose a risk to the safety of patients and act as a source of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs)1.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is widely reported as one of the most common and problematic bacteria in healthcare facilities2,3. Several studies have shown that up to 50% of hospital-acquired P. aeruginosa infections may be derived from the water distribution system3-10.

Even where water meets stringent drinking water quality requirements, it is not sterile, and within days microbial biofilm can develop in water distribution systems, including taps, sinks, showerheads, and tanks11.

Biofilm protects the microorganisms within it from chemical agents and thermal disinfection procedures, and is extremely difficult to eradicate once established12 .

Waterborne human pathogenic microorganisms frequently associated with HAIs include:

- Legionella pneumophila: the cause of Legionnaires’ disease, a potentially fatal form of pneumonia. Risk factors for susceptibility to Legionella include age, illness, immunosuppression, or a history of smoking. It is perhaps the best-known waterborne bacterium colonizing biofilm, and it can be found in both central storage areas (e.g. water tanks) as well as peripheral water outlets in healthcare facilities. Nosocomial (healthcare-acquired) cases of Legionnaires’ disease, have a high case–fatality rate (as high as 40%)13 . A review of 27 Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks investigated by CDC during 2000–2014 indicated that healthcare–associated Legionnaires’ disease accounted for 33% of the outbreaks, 57% of outbreak-associated cases, and 85% of outbreak-associated deaths. In addition, 85% of all Legionnaires’ disease outbreaks were attributed to water system exposures that could have been prevented by effective water management programs14.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a major cause of severe infections, including wound, skin, pneumonia, and sepsis. 51,000 healthcare-associated P. aeruginosa infections occur in the US annually with circa. 400 deaths per year, with 13% being multidrug-resistant15,16.

- Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM): 85,000 people in the US were identified as suffering from NTM infection in 2017. Investigation of healthcare infection risks from water-related organisms (excluding Legionella) through CDC consultations, 2014 – 2017, recorded the greatest number (29.9%) attributed to non-tuberculous mycobacteria17.

Other waterborne microorganisms can also be found in water systems:

- Acinetobacter spp.

- Cryptosporidium spp.

- Klebsiella spp.

- Escherichia coli

- Aspergillus spp.

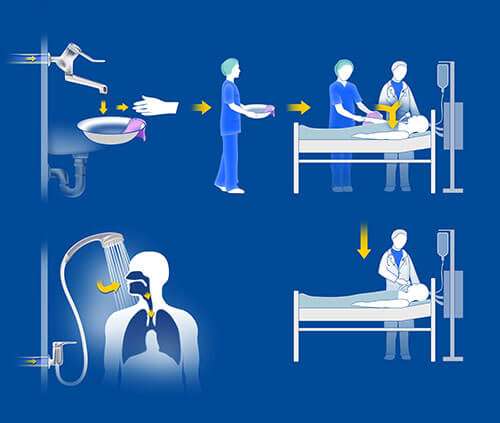

What are the possible infection pathways from water points-of-use to patients?

- Aspiration and inhalation: an established transmission pathway for Legionella spp. Water droplets containing Legionella can form, for example, during shower use, creating an aerosol which may then be inhaled, leading to infection14.

- Direct contact: water for wound care, or the patient’s personal hygiene, may contain bacteria resulting in patient colonization and infection. Pseudomonas spp. is reported to be mainly transmitted by contact, and aspiration. In one study examining 21 faucets in patient rooms, 52.4% were contaminated with a Pseudomonas strain also found in patients18.

- Indirect contact: inadvertent droplet contamination of devices such as catheters, drains and tracheal tubes in ICU patients can occur from health workers’ hands. Rogues et al. reported that 14 % of ICU healthcare professionals’ hands were P. aeruginosa positive when washed with contaminated tap water and 12 % were positive when the last contact was with a P. aeruginosa positive patient18.

- Contaminated drinking water: bottled water or contaminated water from drinking water dispensers has been described as a source of Pseudomonas spp 19-21.

Reducing infection risk by filtration of waterborne pathogens

The large and complex water systems in healthcare facilities can promote the growth of waterborne pathogens. This source of potential pathogens, combined with a resident population who are susceptible to infection, has led the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and CDC consider it essential that hospitals and nursing homes establish a water management program1.

Learn more about managing the risks from waterborne pathogens

Point of Use Filters for Water Infection Control

Pall POU Water Filters are FDA 510(k) Cleared Class II Medical Devices for faucets, showers and ice machines. They are validated to act as a barrier to Legionella spp., Pseudomonas spp., non-tuberculous mycobacteria and other opportunistic waterborne pathogens which may lead to patient infections.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Healthcare Environmental Infection Prevention: Reduce the Risk from Water.” Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/environment/water.html [Accessed 2 June 2020]

- Wunderink and Mendoza, “Epidemiology of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the intensive care unit”, published in “Infectious diseases in critical care”, Springer Verlag, 218-25, 2007

- Vernier et al., “Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition in intensive care units: a prospective multicenter study”, J Hosp Inf, 88:103-8, 2014

- Loveday et al., “Association between healthcare water systems and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a rapid systematic review”, J Hosp Infect, 86(1):7-15, 2014

- Cholley et al., “The role of water fittings in intensive care rooms as reservoirs for the colonization of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa”, Intensive Care Med, 34:1428-33, 2008

- Blanc et al., “Faucets as a reservoir of endemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization/infections in intensive care units”, Intensive Care Med, 30:1964-8, 2004

- Vallés et al., “Patterns of colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in intubated patients: a 3-year prospective study of 1,607 isolates using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis with implications for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia”, Intensive Care Med, 30:1768-75, 2004

- Rogues et al., “Contribution of tap water to patient colonisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a medical intensive care unit”, J Hosp Infect, 67:72-8, 2007

- Walker et al., “Investigation of healthcare acquired infections associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in taps in neonatal units in Northern Ireland”, J Hosp Infect, 86(1):16-23, 2014

- Walker and Moore, “Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospital water systems: bioflms, guidelines practicalities”, J Hosp Inf, 89(4):324-27, 2015

- Exner et al., “Prevention and control of healthcare-associated waterborne infections in health care facilities”, Am J Infect Control, 33: S26-S40, 2005

- Flemming and Wingender, “The bioflm matrix”, Nat Rev Microbiol, 8:623-33, 2010

- World Health Organization, “Legionella and the Prevention of Legionellosis“, 2007, ISBN 92 4 156297 8 Available at: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/emerging/legionella.pdf [Accessed 2 June 2020]

- Soda et al. “Vital Signs: Health Care–Associated Legionnaires’ Disease Surveillance Data from 20 States and a Large Metropolitan Area — United States”, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:584–589. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6622e1. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6622e1.htm [Accessed 2 June 2020]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Healthcare Settings”. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/organisms/pseudomonas.html [Accessed 2 June 2020]

- Jefferies et al., “Pseudomonas aeruginosa outbreaks in the neonatal intensive care unit – a systematic review of risk factors and environmental sources“, Journal of Medical Microbiology, 1052–1061, 2012

- van Dijket al. “A multimodal regional intervention strategy framed as friendly competition to improve hand hygiene compliance.” Infection control and hospital epidemiology 40,2 2019: 187-193. doi:10.1017/ice.2018.261

- Rogues et al., “Contribution of tap water to patient colonisation with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a medical intensive care unit“, J Hosp Infect 67, 1: 2007 72-78

- Eckmanns et al., “An outbreak of hospital-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections caused by contaminated bottled water in intensive care units”, Clin Microbiol Infect, 14:454-8, 2008

- Wong et al., “Spread of Pseudomonas fluorescens due to contaminated drinking water in a bone marrow transplant unit”, J Clin Microbiol, 49:2093-6, 2011

- Costra et al., “Nosocomial outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated witha drinking water fountain”, J Hosp Infect, 91:271-4, 2015